The names of many of the great lakes of the South Island were given by the ariki of the Uruao canoe, Rākaihautū, who traversed the island with his famous kō and 'created' (named) the southern lakes of the interior and also the coastal lakes and lagoons of the east coast. While Rākaihautū was exploring the interior of the South Island, his son, Rokohouia, sailed the Uruao down the east coast, meeting up with his father at Waihao in what is now South Canterbury before the party returned north to Banks Peninsula.

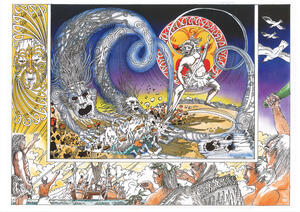

Illustration by Cliff Whiting

In South Island legends, Rākaihautū is identified as the person who traversed the land, naming the lakes as he went. He and his son Rokohouia were the ariki (leaders and guardians) of the canoe Uruao, one of the earlier canoes (before the canoes of the so-called 'fleet') to arrive on the shores of Aotearoa.

The Uruno made landfall at Whangaroa in the north. The people of the Uruao surveyed the land of Muriwhenua, sometimes called Te Hiku o Te Ika a Maui (The Tail of the Fish of Maui). They discovered that many who had arrived in Aotearoa earlier than themselves had settled there. The desire to find land for themselves prompted them to move on. They sailed southward, following the west coast, finally making landfall at Whakatū (Nelson). Here they decided that the only effective way to survey the land would be to divide themselves into two groups, one under the leadership of Rākaihautū who would traverse the land and the other under the leadership of Rokohouia who would explore the island's coasts by sailing through Raukawa Moana (Cook Strait) and down the east coast through Tai ō Marokura (the Ocean of Marokura), the seas off the Kai Kōura Coast.

Rākaihautū, with his kō (wooden spade) named Tu Whakarōria, set off into the forest on the first leg of his journey. Some distance from Whakatū he dug two enormous trenches with his kō. The trenches filled rapidly with water. The larger of the two bodies of water he named Rotoroa, the other he name Rotoiti. Thus began Rākaihautū's enormous task, the creation/naming of the lakes of Te Waka a Aoraki (The Canoe of Aoraki, the South Island), from this beginning near Raukawa Moana down to the shores of Te Ara a Kewa (the Pathway of Kewa, Foveaux Strait) and on to a final ending of his journey at Banks Peninsula.

As Rākaihautū made his way southwards he created and named lakes, Hoka Kura, (the red promontory or rocks) Lake Sumner, Whakamātau, (the meaning is obscure) Lake Coleridge, and ō Tūroto (the lake of Tūroto, a member of the party) Lake Heron. He and his party moved on southwards along the ranges until they reached the next group of lakes on the eastern side of the Alps. He named these Iakes Takapō (to move about at night), the lake now known as Tekapō (Tekapō has the meanings of lightning, or a species of eel, but Takapo is the correct name), Pūkāki (the source), ō Hau (of Hau, a member of the party) and Hāwea (another member of the party whose full name was Hāwea Ki Te Rangi and who belonged to the people known as Hāwea).

Still moving southward, Rākaihautū and his companions arrived at a place which he decided was an appropriate place to perform the rituals which would ensure their continued safety. They marked that place by naming the lake there Wānaka (the lore of the tohunga or priest).

Further south again, he came upon the great lake which he named Whakatipu Waimāori (waimāori means fresh water). This is today's Lake Whakatipu. The party then veered to the west and crossed a range which Rākaihautū named Kā Mauka Whakatipu (kā mauka means the mountains), the Ailsa and Humboldt Mountains. Beyond these mountains they found and named another large lake Whakatipu Watai (waitai means salt water). This is Lake McKerrow. On the eastern side of Kā Mauka Whakatipu is Te Awa Whakatipu, the Dart River, which flows into Whakatipu Waimāori, while the river which has its source on the western side of Ka Mauka Whakatipu and flows into Whakatipu Waitai is named Whakatipu Kā Tuka, the Hollyford River. This cluster of 'Whakatipu' names, grouped together as they are, poses a problem for historians, Māori and Pākeha. The word 'whakatipu' is an ancient one and its meaning as it is used in these place names is obscure. Attempts have been made to translate the word, or variations of it, but these attempts demean the ancestor Rākaihautū. lt is better simply to let the names stand, unexplained until, if ever, someone with profound knowledge can elucidate the meaning or origin of 'Whakatipu'.

After naming these Whakatipu features, Rākaihautū and his party turned inland and began heading south again. They found a large and beautiful lake which they named Te Ana Au (cave of rain) and just south of it another lake which Rākaihautū named Roto Ua (the lake where rain is constant). The two names suggest the party encountered wet weather in the area. The lake which was named Roto Ua is today mistakenly called Manapouri, a Pākeha corruption of Manawa Popore, the original name of North Mavora Lake. It is known by the Māori of that region as Motu Rau, says Tipene O'Regan. The word 'Manapouri' defies translation.

Rākaihautū and his party continued on to the south until they reached the bottom of the South Island, where he left two people to guard these southernmost parts of the island, where the ocean is known as Te Ara a Kewa (the pathway of Kewa), Foveaux Strait. The rest of the party turned northwards, naming lakes as they moved up the eastern side of the island: Roto Nui A Whatu (the large lake of Whatu); Waihora (spreading waters) is familiar in the slightly changed form of Warhola; Kai Kārae (the eating of a type of seabird, kārae) is the lagoon at the mouth of the Kaikorai Stream. At Waihao (the waters of a species of eel known as hao) the weary party led by Rākaihautū met up with Rokohouia and his party who were gathering the hao eels from the lake. The reunion was joyful. The lake Waihao is known today as the Wainono Lagoon, near the mouth of the Waihao River.

Rokohouia had sailed the Uruao through Raukawa Moana and down the east coast of the South Island through Tai ō Marokura until he came to Kai Kōura. The full name of this place is Kā Ahi Kai Kōura a Tama Ki Te Rangi (the fire on which Tama Ki Te Rangi cooked his crayfish). Rokohouia and his party stayed at Kai Koura for some time, supplementing their seafood diet with seagull eggs which were collected in large numbers from the high cliffs around Kai Koura. These cliffs were known from that time as Kā Whatakai A Rokohuia (the foodstores of Rokohouia). As Rokohouia moved further south from Kai Kōura he noted the mouths of the rivers and studied the migratory habits of the eel and lamprey. He drove sturdy posts into the beds of the rivers at their mouths and constructed eel and lamprey weirs around them. Hence the many rivers and coastal lakes and lagoons north of and including Waihao are known collectively as Kā Poupou A Rokohouia (the posts of the weirs of Rokohouia).

After a period of rest at Waihao, the reunited party decided to move north to Akaroa (long bay), which would be Whangaroa in the northern dialects. To reach Akaroa, the party had to cross the Canterbury Plains. The original name of the plains was Kā Pākihi Whakatekateka A Waitaha (the seed bed of the Waitaha people). The plains are still known by this name to the Kāi Tahu people today.

At the northern end of the plains, they came upon a large shallow lake which they called Waihora (spreading waters), a name which Rākaihautū had already given to another Iake further south, Waihora or Waihola. This more northern Waihora was centuries later renamed Lake Ellesmere. Another old name for this lake, still used by the local people, is Te Kete Ika A Rākaihautū, the fish basket of Rākaihautū, a reference to its abundance of flounder and eel. Not far from Te Waihora is Wairewa (the meaning of this name is obscure; rewa can mean to float, to become liquefied, to raise, or elevated). Wairewa was also renamed centuries later, Lake Forsyth.

Rākaihautū's task of creating/naming the lakes of the South Island ended here. He therefore decided he would create a memorial to his work for all time. He climbed a high hill named Puhai, overlooking his lakes and the plains to the south and Akaroa to the east. On the summit of this hill, he plunged his faithful kō, Tu Whakarōria, firmly into the ground and left it there to adorn the skyline. The hill was renamed Tuhirangi (adorning the skyline). Rākaihautū lived out the rest of his life at Akaroa.

Time has not diminished Rākaihautū's fame.

His sacred footprints remain along the lines of his famous lakes, many of which retain to this day the names he bestowed on them. Collectively, the lakes are known as Kā Puna Karikari A Rākaihautū (the springs of water dug by Rākaihautū).

Place names from Rākaihautū's journey

Roto Roa

Long lake

Roto Iti

Small lake

Hoka Kura

Red promontory or rocks

Whakamatau

(Meaning obscure)

ō Tūroto

Of Turoto (a member of the party)

Takapō

To move about at night

Pūkāki

(Meaning obscure)

ō Hau

Of Hau (a member of the party)

Hāwea

Hāwea Ki Te Rangi (a member of the party)

Wānaka

The lore of the Tohunga/Priest

Whakatipu Waimaori

Fresh water

Kā Mauka Whakatipu

Mountains

Whakatipu Waitai

Salt water

Te Awa Whakatipu

The river

Whakatipu Kā Tuka

(The meaning of Ka Tuka is obscure)

Rota Nui a Whatu

The large lake of Whatu

Waihora

Spreading water

Kai Kārae

To eat kārae {a seabird}

Waihao

The water of hao (a type of eel)

Kā Whatakai a Rokohouia

Rokohouia's storehouse

Kā Poupou a Rokohouia

The (weir) posts of Rokohouia

Kā Pakihi Whakatekateka a Waitaha

The seed bed of Waitaha

Waihora

Spreading water

Wairewa

(Meaning obscure)

Tuhirangi

Adoming of the skyline

Te Kete Ika a Rākaihautū

The fish basket of Rākaihautū

Kā Puna Karikari a Rākaihautū

The springs of water dug by Rākaihautū

Te Ana Au

Cave of rain (in Kāi Tahu dialect)

Roto Ua

Lake where rain fell constantly

Reproduced courtesy of the New Zealand Geographic Board copyright.